Humans have spoken for hundreds of thousands of years, while writing is a relatively recent invention. He started drawing pictures in caves and elsewhere to represent his thoughts, speeches, and records. The earliest cave paintings in Europe are considered to be about 37,000 years old. In 2011, archeologists discovered a rock drawing in Blombos cave, South Africa, dating back 73,000 years.

It was challenging to convey all his thoughts through pictures, so he tried to simplify pictures and created symbols to represent sounds and ideas. It is difficult to accurately predict when man started drawing up symbols to convey sounds and thoughts, but symbols started appearing along with rock paintings approximately 10 thousand years ago.

A script is a crucial tool for tracking the development of any civilisation because it allows people to convey speech, ideas, as an aid to memorise, and to preserve religious hymns. Historians classify the past time into prehistoric and historic periods. Anything prior to the development of a writing system is referred to as the prehistoric period, whereas the historic period is defined as the time frame during which written materials became available.

Then, when does India’s historic period begin? Or what ancient Indian writing system has been discovered and fully comprehended by contemporary historians? Up till now, Brahmi has been the response. After deciphering the Indus script, however, we can say that India’s history began at least with the Indus Valley civilisation (3300 BCE–1300 BCE), which is comparable to, if not as old as, the advanced civilisations of Egypt and Mesopotamia during that time.

Discovery of the Indus Valley Civilisation

The civilisation of the Indus Valley (3300-1300 BC) is considered one of the three earliest civilisations in world history, along with Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Five thousand years ago, the Indus Valley civilization held an estimated one million people spread over a region stretching from Pakistan and north-western India, covering more than 800,000 square kilometres with thousands of settlements. Its largest excavated cities, Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, exhibit levels of urban planning that rival modern cities, including a dense network of streets within strong city walls, granaries to store food, and the world’s earliest system of sanitation and water supply with wells, bathing rooms, and covered drains. Houses had sleeping and cooking areas, courtyards, and upper stories.

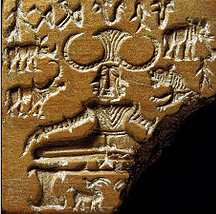

However, the Indus civilisation is best exemplified by its miniature seals, of which thousands were discovered during the excavations of various sites in India and Pakistan.

Indus seals and inscriptions

Excavation at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro produced a large number of seals. They are generally square, with sides approximately an inch long. Seals display the script on the top and an animal motif at the centre. These seals were carved out of soapstone and fired to make them more durable. A wide variety of animals were depicted on seals, including unicorns, zebu, buffalos, goats, deer, rhinoceros, elephants, and tigers.

The ‘unicorn’ motif is placed first because it is the most common one of the Indus seals. Approximately half of the discovered seals represent the Unicorn.

Since the 1920s, more than 100 attempts have been undertaken by professional scholars, archaeologists, and epigraphists to read the inscriptions written on these seals. This list includes Sir Alexander Cunningham, J. F. Fleet, John Marshall, G.R. Hunter, A.H. Dani, A. Parpola, and I. Mahadevan.

However, all attempts resulted in failures. Three reasons are attributed to these failures:

- First, no firm information is available about its underlying language. Was the script an ancestor of Sanskrit or Dravidian, or a language that had now disappeared?

- Second, there is no Indus bilingual inscription comparable to the Rosetta Stone and the Behistun inscription have enabled the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphics and the cuneiform script of Mesopotamia.

- Third, Indus inscriptions are very short. There are approximately five characters per seal.

Few researchers suspect that the Indus script may not be capable of expressing a spoken language. In 2004, historian Steve Farmer, computational linguist Richard Sproat (now a research scientist at Google), and Sanskrit researcher Michael Witzel from Harvard University compared the Indus script with a system of non-phonetic symbols akin to those of the Neolithic Vinča culture.

Was there any historical account of the Indus script?

Although modern scholars have been studying this undeciphered script for over 100 years, a fascinating account comes from the writings of a Chinese monk who came to India approximately 1500 years ago. Xuanzang, also known as Huen Tsong (602–664 AD), was a Buddhist monk who travelled from China to India in the seventh century. Xuanzang leaves a detailed account of various Central and South Asian countries, their culture and geography, and his central theme, i.e., works on Buddhist religion.

According to Xuanzang, “Their system of writing was invented by Brahma, who instituted as patterns forty-seven [written] words at the beginning. These were combined and applied as objects arose and circumstances occurred; ramifying like streams, they spread far and wide, becoming modified a little by place and people….. The people of neighbouring territories and foreign countries repeating errors until these became the norm, and emulous for vulgarities, have lost their pure style. …. Disgusted with the bad treatment given to these letters, he swallowed them all”.

Xuanzang was right about Brahma’s swallowing (i.e., script being lost). The script was entirely lost, though its faint memory remained in folklore.

During the 19th century, many European scholars tried to decipher extinct scripts around the world. The oldest script ever discovered in India was found on the inscriptions of Asoka (reign 268–232 BC). It was concluded that this script “must have been the first kind of writing used when Sanskrit literature began to be written down [perhaps six centuries BC]”. This assumption led to naming this script (used on the Asoka inscription) as the Brahmi script to associate it with the popular belief that Brahma was the inventor of the first script.

To this date, based on archaeological evidence, the majority of scholars believe that the first alphabet system was invented by the Phoenicians (approximately 1600 BC) and that Greeks, Romans, and Indians improved upon the Phoenician’s writing system by introducing explicit vowels to suit the phonetics of their spoken languages.

After observing the Indian Devanāgarī script with thirty-five consonants and sixteen vowel symbols, Monnier Williams observed: “the modest equipment of twenty-two letters which satisfied the Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans, to whom the invention of writing was a mere human contrivance for the attainment of purely human ends, could not possibly have satisfied the devout Hindu, who regarded his language as of divine origin…of course, a system of writing so highly elaborated was only perfected by degrees”.

The awe felt by Monier Williams at a glance of the Devanāgarī script is understood, but unfortunately, he was not alive to see a glimpse of real Brahmi script (not the script written on Asoks inscriptions, which were popularised and marketed as the “Brahmi script”) that included vastly more numbers of vowels, consonants. The lost script of Brahma, the oldest script in the world, was waiting for divine intervention to bring it back to life.

The divine intervention

It was 21st March 2019, a Nawroz day (literally “New Day”), and I encountered a blessing that enabled me to decipher the oldest script in the world. The Nawroz day is the day of the vernal equinox, which marks the beginning of Spring in the Northern Hemisphere, where the sun completes its cycle of passing through all the “celestial stations”, which are known as the Zodiac signs, and enters the first station, known as “Aries” in Western culture (or “Haml” in Persian culture).

On a Nawroz day, while returning after performing his last Hajj rites, Prophet Mohammad, Peace Be Upon Him (PBUH) delivered his last sermon at a pond near Khumm shortly before leaving this world. Calling up Imam Ali Alayhi As-Salaam (AS) and taking him by the hand, Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) then gave the famous proclamation “Anyone who has me as his master has Ali as his master”, and the day was the 18th Zilhij 10 Hijri, a Nawroz day. On 21st March 2019, the Nawroz day coincided with another memorable day of the Arabic calendar, the 13th Rajab 1440 Hijri, an auspicious day when Imam Ali (AS) was born.

I was watching a video on YouTube. In that video, a Muslim scholar spoke of a prophet who could talk to birds. As a faithful, my mind reasoned that if it were an animal, one could sense its emotions (body language), but communicating with a bird is impossible except when someone is blessed by Imam Ali or by his son Imam Husain (AS), as desired by Allah.

After watching the video, I started reading “Account of Yuan Chwang’s Travels”. When I reached a page where Yuan Chwang mentions Brahma swallowing his script, I said to myself, “No one but Imam Husain (AS) could make someone read what he does not know”. But this faith came along with a high awareness mode, with a feeling that cannot be explained in words, with hidden secrets revealed to me as if they were in front of my eyes. A thought came into mind: what if the Indus script was the lost script of Brahma? I did a web search for the Indus script and saw images along with the script. There was an image of a bull with three lines followed by a trident-like symbol (refer to ANNEX – 16). A word was put in my mind. This single word was like a free end, given to me to untangle the Indus script’s Gordian knot.

The help did not end there. Another idea that came to mind was to compare the most frequently occurring symbols of the Indus script with the most frequently occurring letters of the Rigveda, the oldest Sanskrit book. If two scripts represented the same language, then in an ideal scenario, the most frequently used letters of the Indus script would correspond to the most frequently used letters of the Rigveda.

The decipherment process had started, and I could read many words within a few hours.

My daughter Insiya came out of her room and asked, “What the hell are you doing at 1 am? Go and sleep”! I went to bed and thought that the “blessing of Mohammad P. B. U. H. and his family, especially that of Imam Husain AS, had given me the key to reading something I did not know four hours ago”.

(All blessing of God ends at the last prophet, onwards, mercy will flow from his house).

Reasons why I succeeded while other failed to decipher the Indus script

There were a number of reasons why was I able to decipher the Indus script were following:

A miracle that gave me a correct starting point to start; while the majority of previous decipherment attempts had failed as they had associated the fish symbol with “M”.

Additionally, I made:

- correct assumptions,

- used proven methodologies and

- was able to see similarities various Indian scripts and could link it to the Indus script.

We need to know a bit about the characteristics of the Indus script that will enable readers to better appreciate why there were so many symbols (around 800) which could not be mapped against any known Indian scripts.

| Indus script | Brahmi and other Indian scripts | |

| Number of symbols or letters | Approx. 800 | Less than 60 |

| Direction of writing | Right to left | Left to right (Exceptions: Karoshti, Urdu and Sindhi) |

| Conjuncts | Two or more consonants and vowels can merge to form a conjunct | Two consonants can merge to form a conjunct |

| Number of vowels | Very large number of vowels and diphthongs | Less than 15 |

| Vowels | The Indus script allows consecutive vowels | Consecutive vowels are not allowed (Sandhi rule applies) |

| Second series of consonants | The Indus script has a second series of consonants | None of the Indian script has such feature. Tocharian script has a second series of consonants. |

Additionally, Indus has two extraordinary features, which none of the Indian scripts has:

- Variations in consonants and conjuncts were organized in a very systematic manner. These variations were responsible for Indus script to have a large number of symbols. Their large numbers made other scholars fail to map them against any known Indian script. On other hand they were organized in a very systematic manner, which helped me to decipher the Indus script.

- Symbols (for conjuncts) of the Indus script had many hidden clues that enabled me to decipher this script.

Implications of this decipherment:

Implications of this decipherment (from linguistic point of view):

The outcome of the decipherment was unexpected:

- The underlying language was the Sanskritized version of the Prakrit languages (similar to Pali).

- It turned out to be employing Pre-Panini Sanskrit, known as Aindreya’s system. Which at this moment in time no one knows except me due to this decipherment.

- This script has many sounds that were lost in the classical Sanskrit, such as the sound of “W,” which does not exist in any Indian language and is pronounced as “V.” A second H was also identified that provides direct evidence of Laryngeal theory to be correct. In addition, the decipherment identified the existence of a second Y sound, which does not exist in Sanskrit. Andrew Shiller, a well-known linguist had predicted this sound as a missing sound of Vedic Sanskrit when he compared the Vedic texts against Zoroastrian religious texts.

- It also contains a lot more vowels than any other alphabet in the world, with many of them grouped in numerical formulas. From the perspective of a linguist, it will have extremely important implications. We are close to reconstructing a language that could be categorised as Proto-Indo-European (PIE).

Implications of this decipherment (tracing Aryan migration routes)

Taking into account that the Indus script has notable Prakrit language traits, which can only be the case if the language’s speakers (Aryans) have lived in the Indus Valley for a minimum of a millennium. It then begs the question, where did the Aryans come from? This book combines archaeological, genetic, and linguistic evidence to trace ancient Aryan migrations that resulted in the spreading of various Indo-European languages. Results of this analysis reject the popular Kurgan hypothesis proposed by Marija Gimbutas and emphasise that these were the Aryans, who established “old Europe” and started farming practices.

Implications of this decipherment (cultural)

The most captivating experience is reading an inscription that is 5,000 years old and has multiple stories to bridge the gaps between myth and history. Stories that many seals have to tell help to unravel the secrets of the ancient civilisation